From Wireless Communication to Precision Motor Control

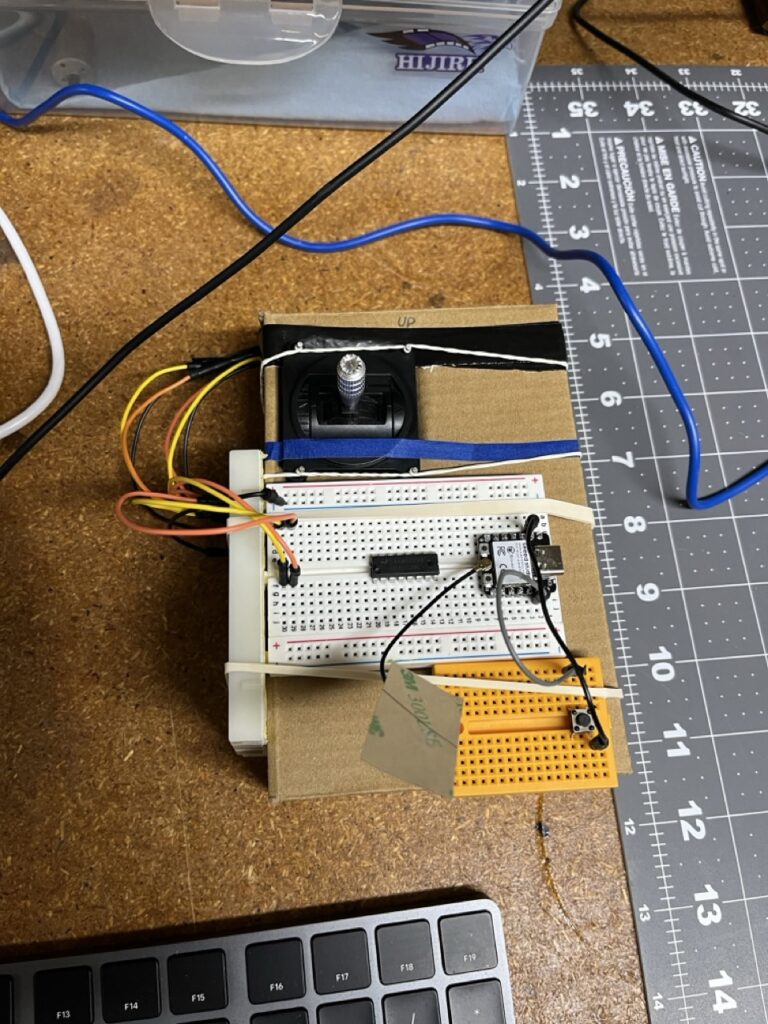

After wrestling with RP2040 boot sequences and bare-metal register programming, I needed a project that would synthesize everything learned while pushing into genuinely uncharted territory. The Earth Rover emerged as that challenge: a modular, extensible rover system built around proven embedded technologies but demanding new levels of integration complexity.

System Architecture Overview

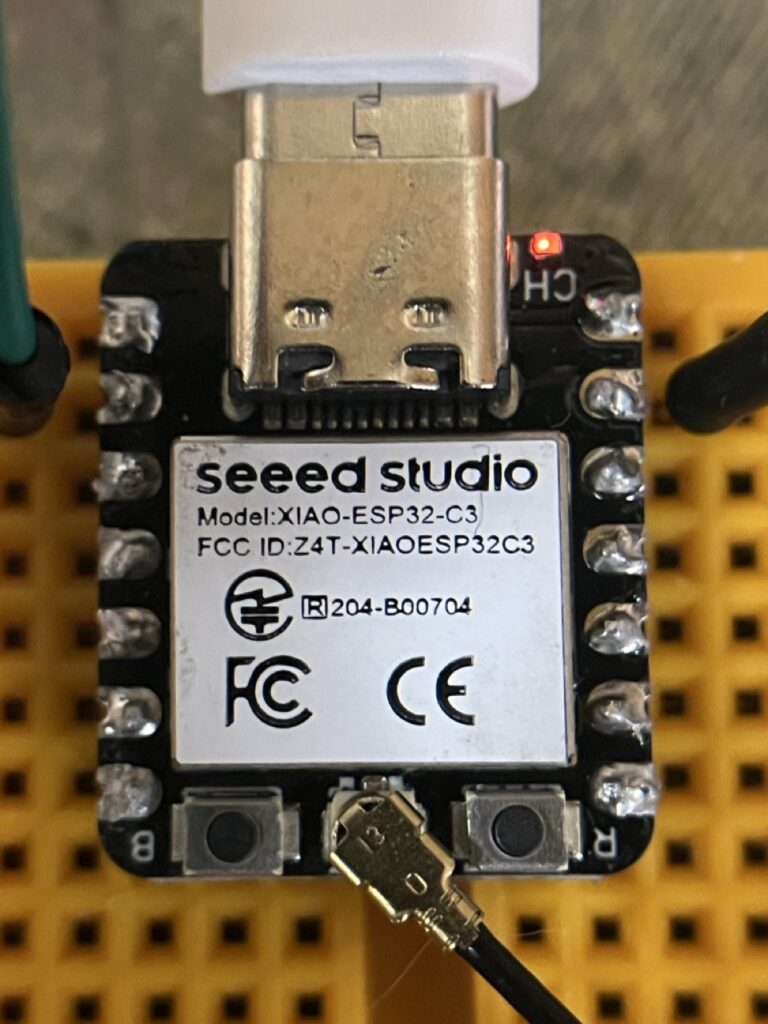

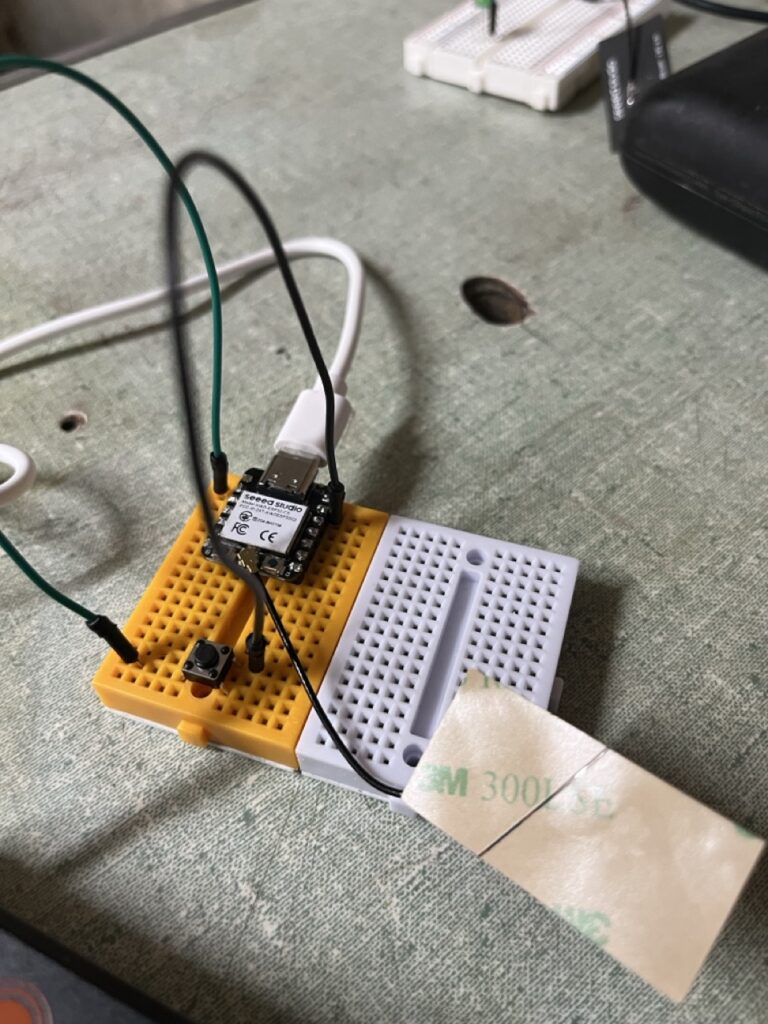

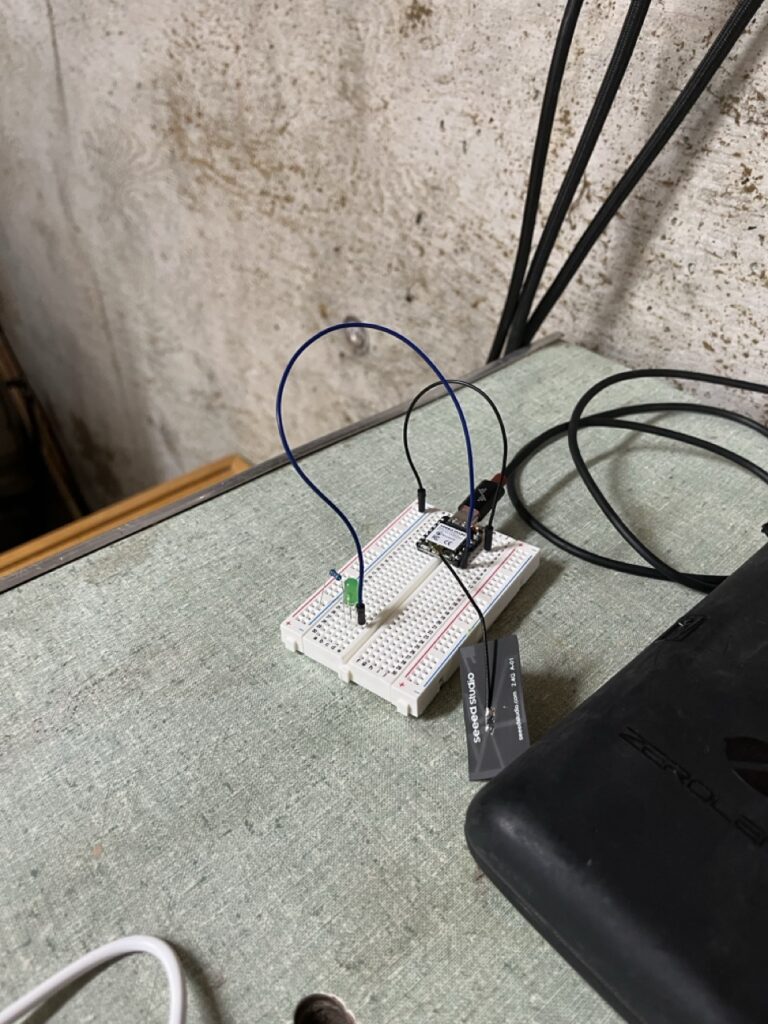

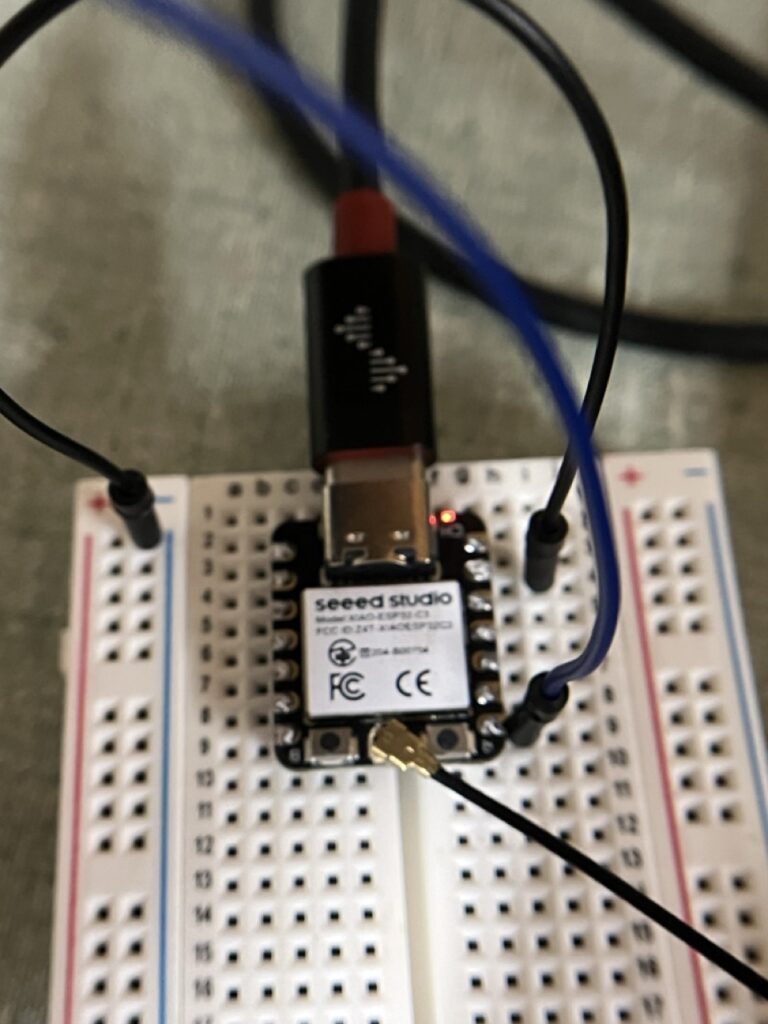

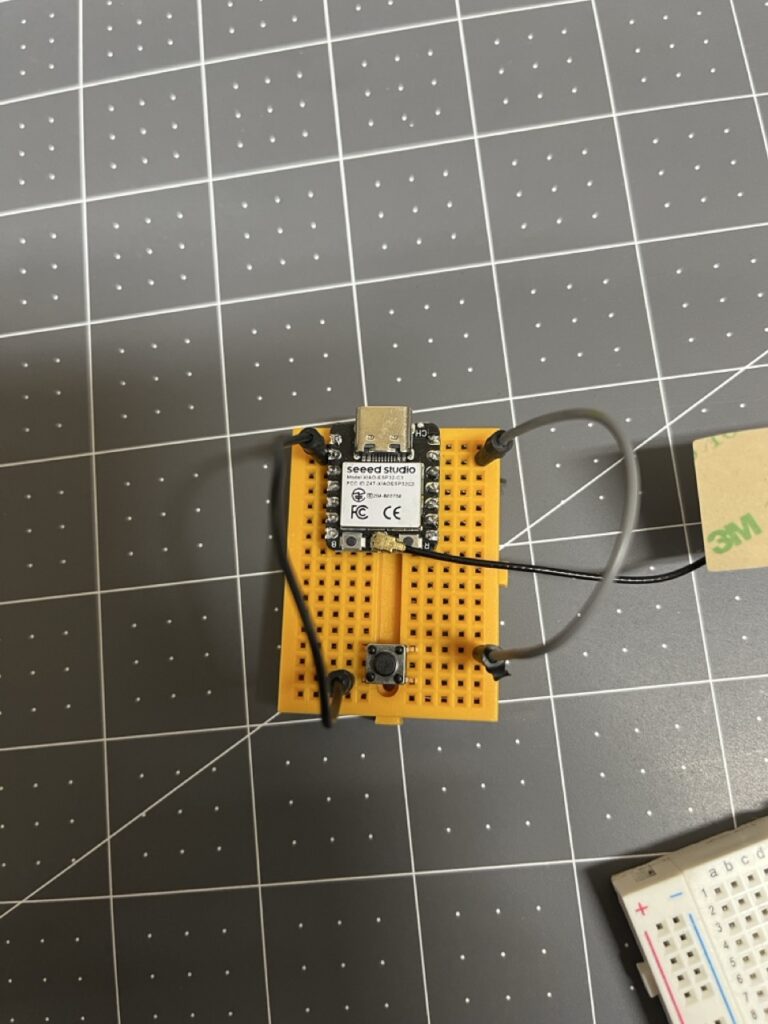

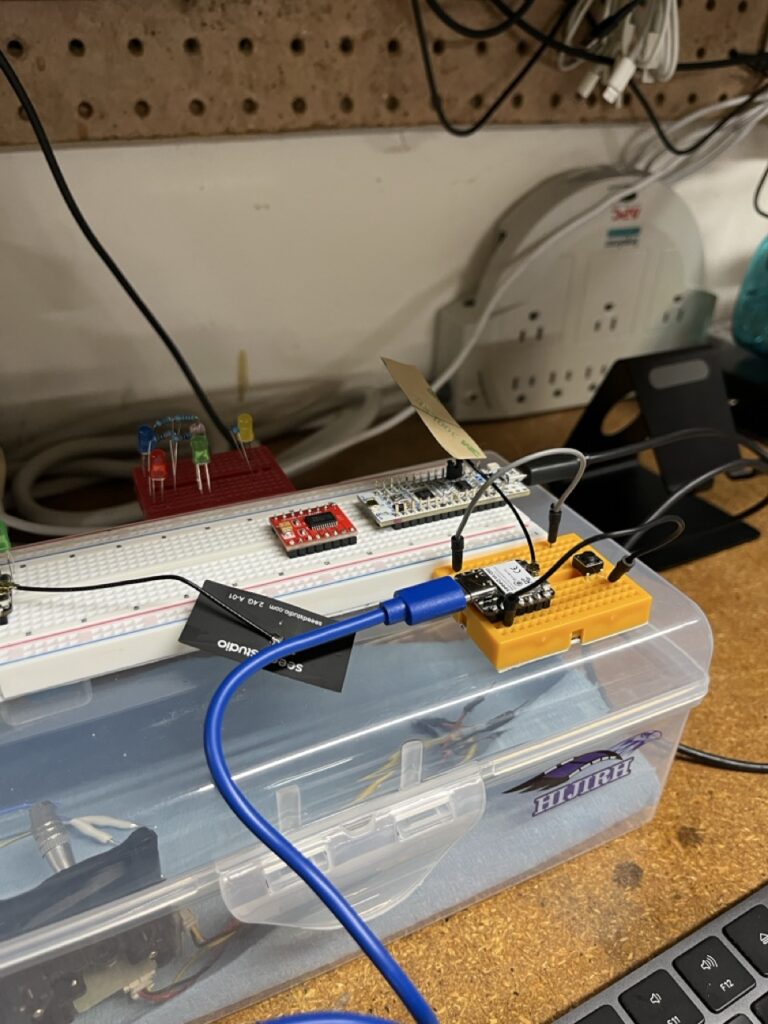

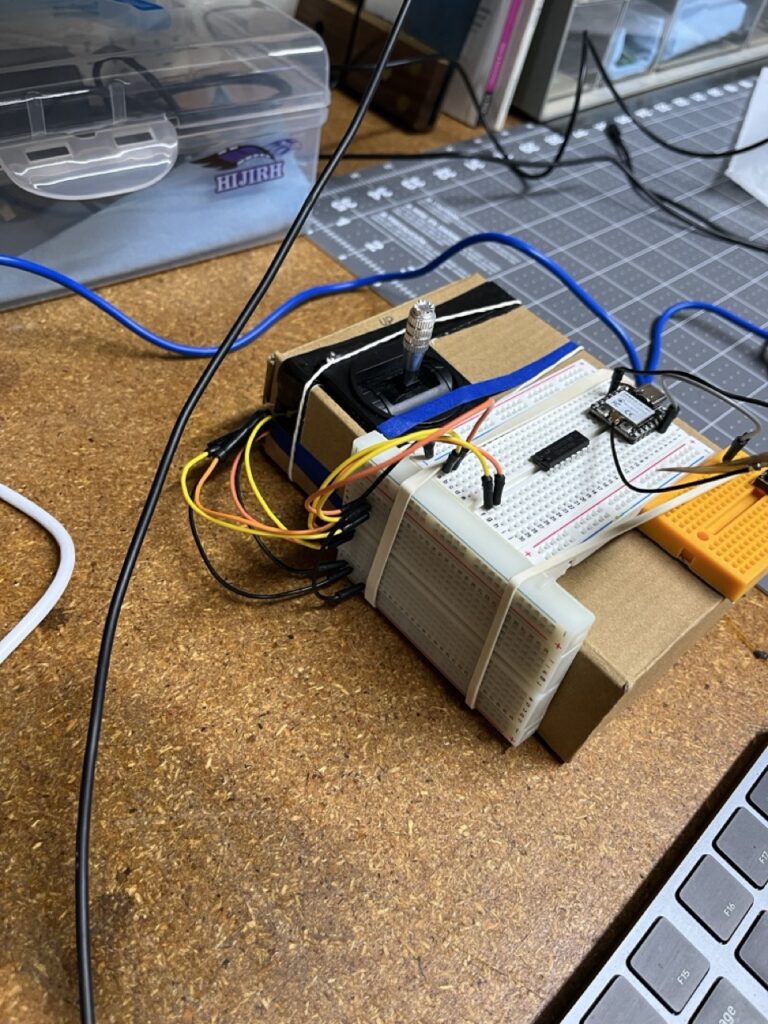

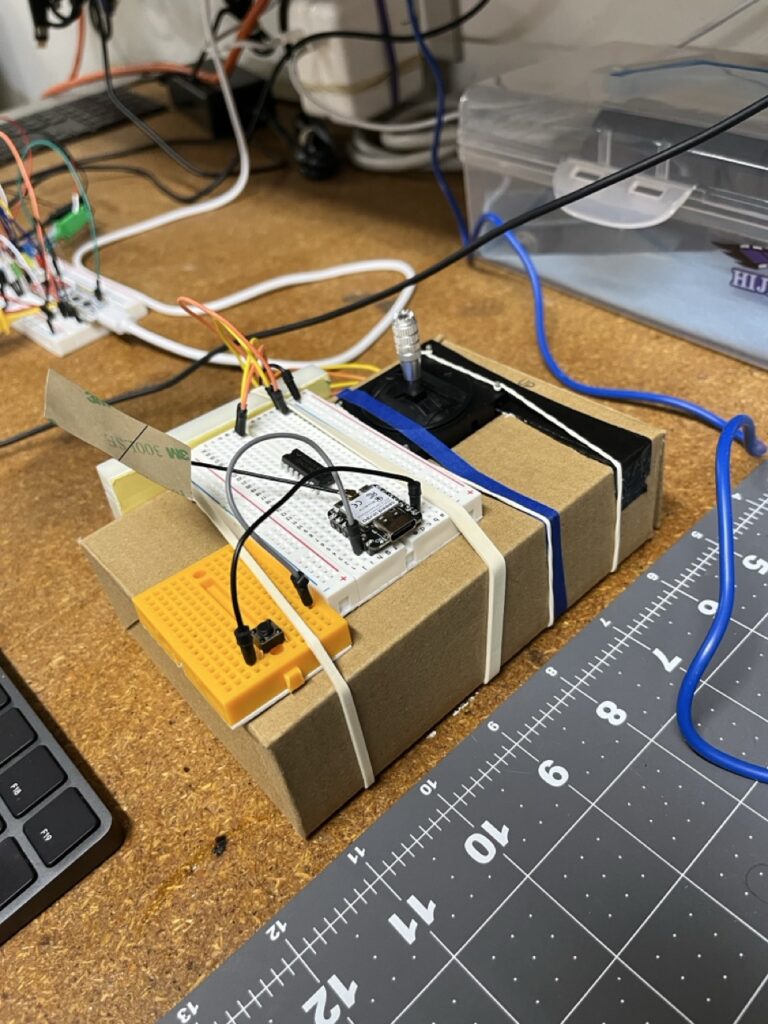

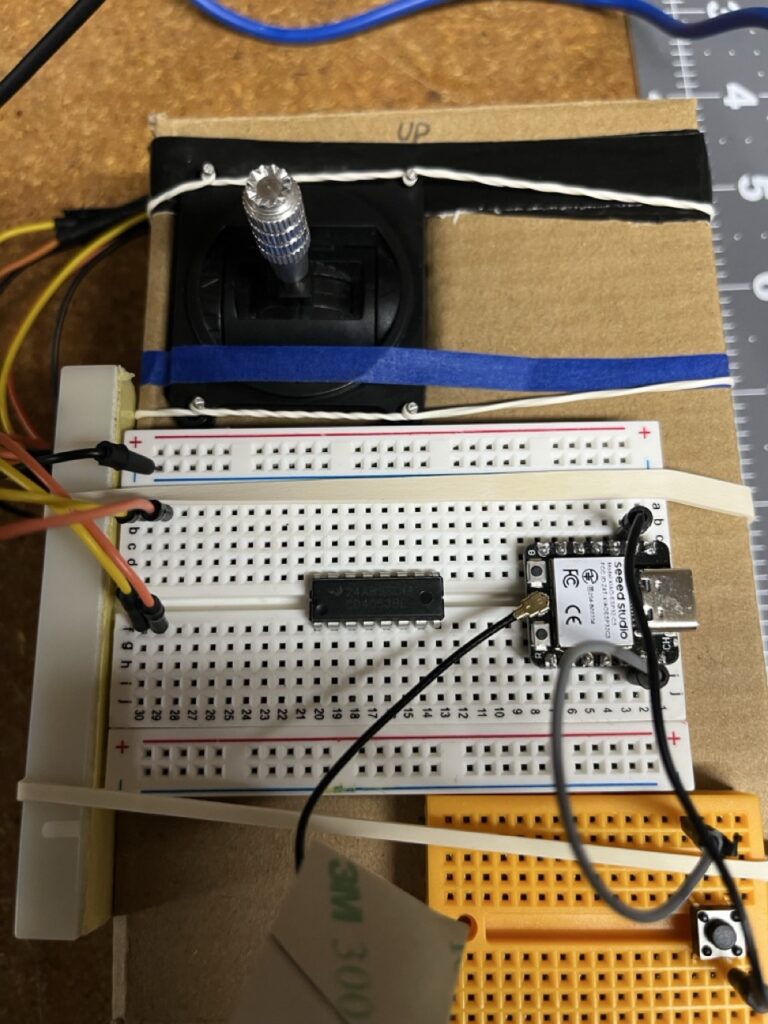

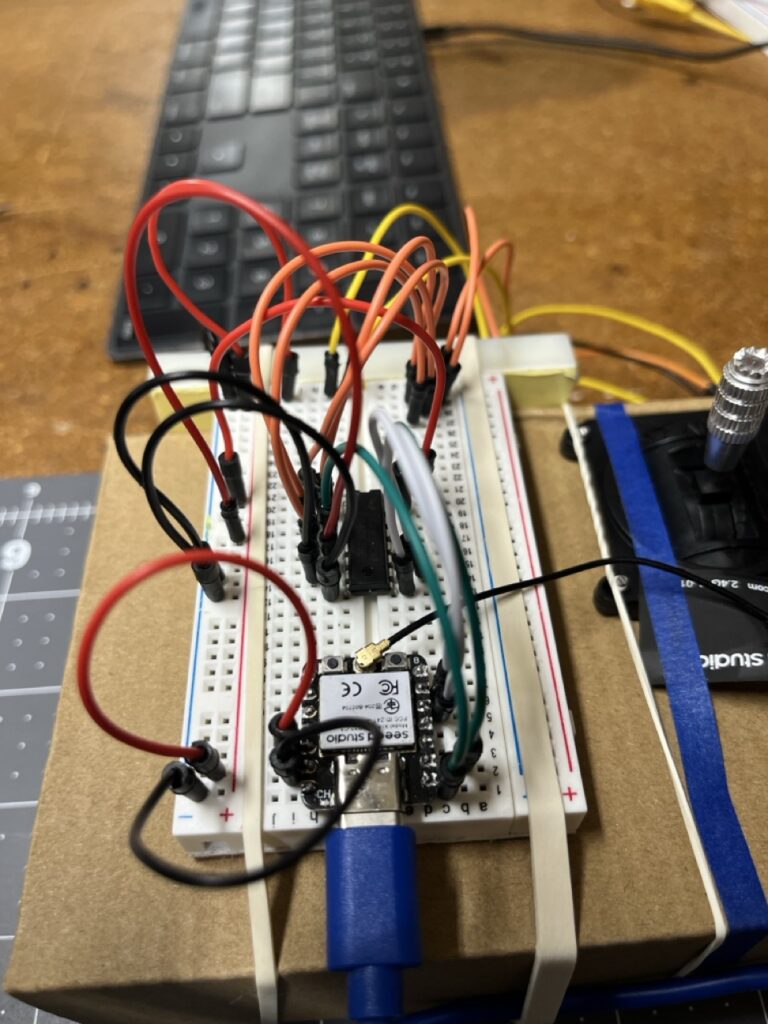

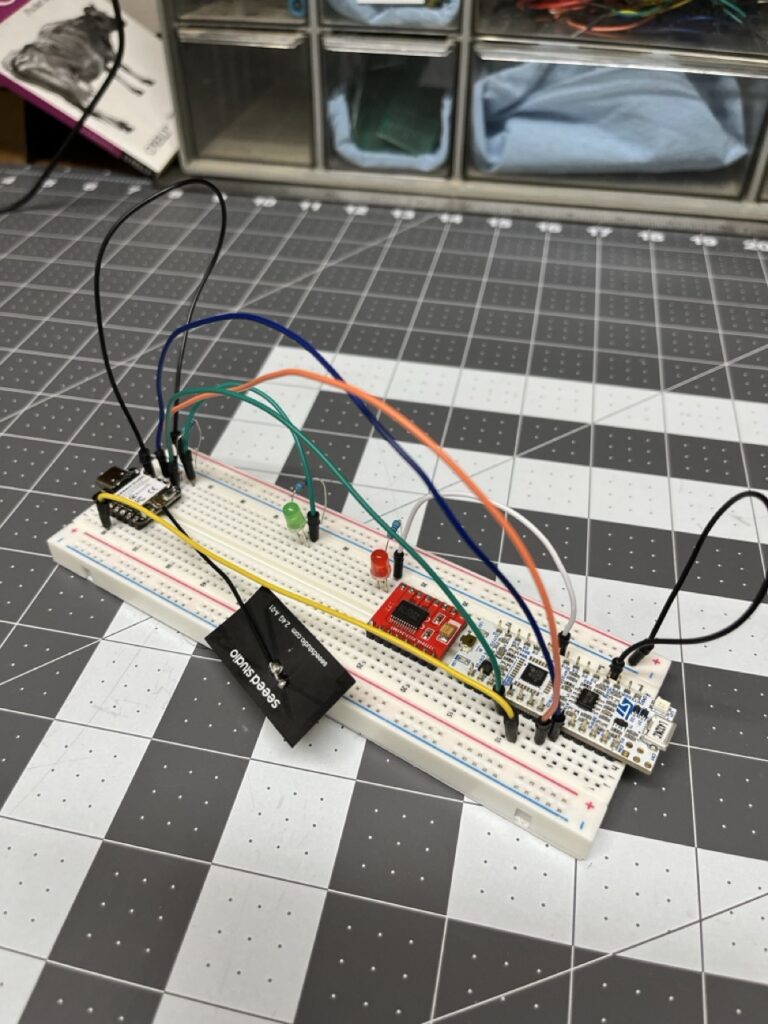

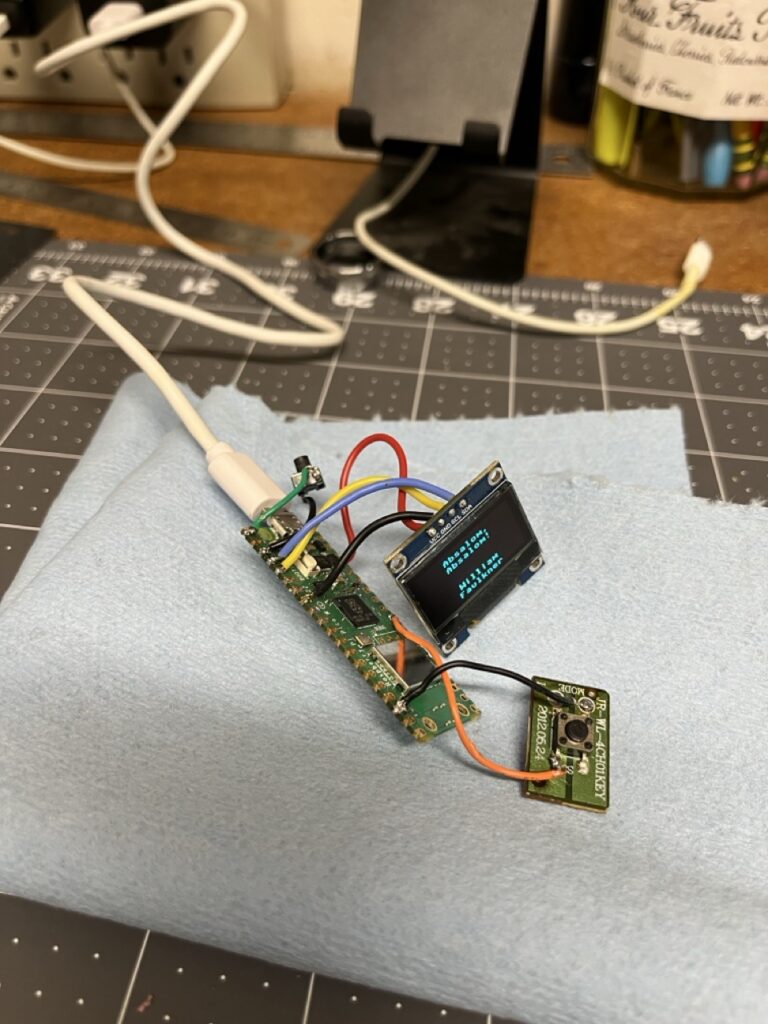

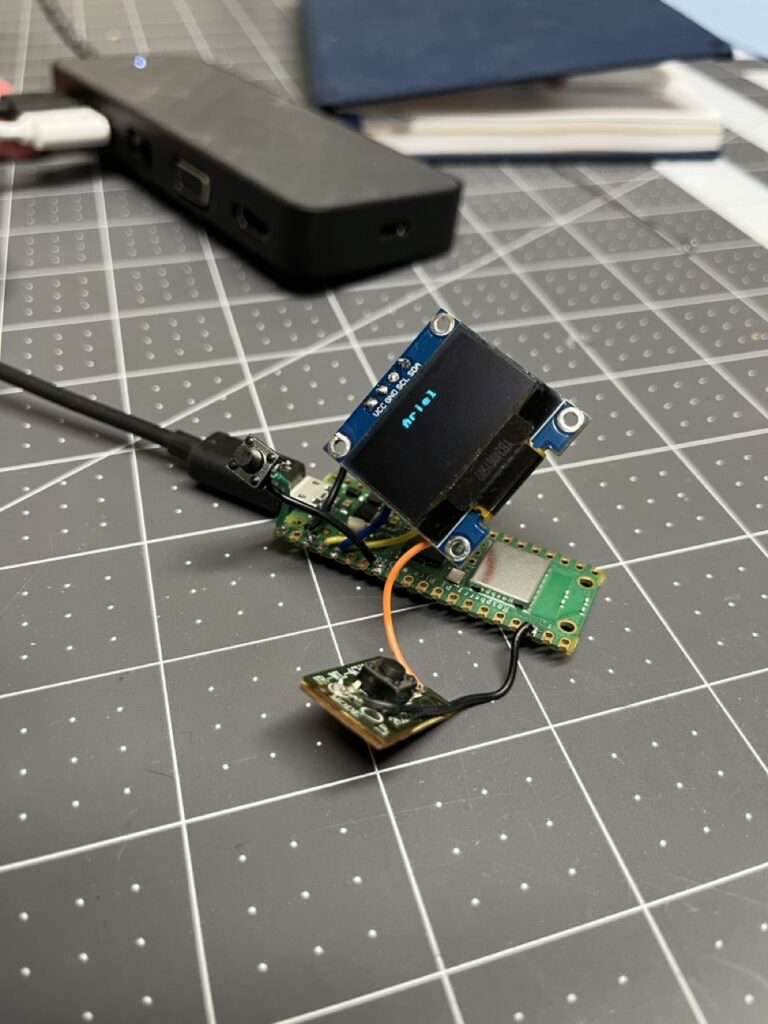

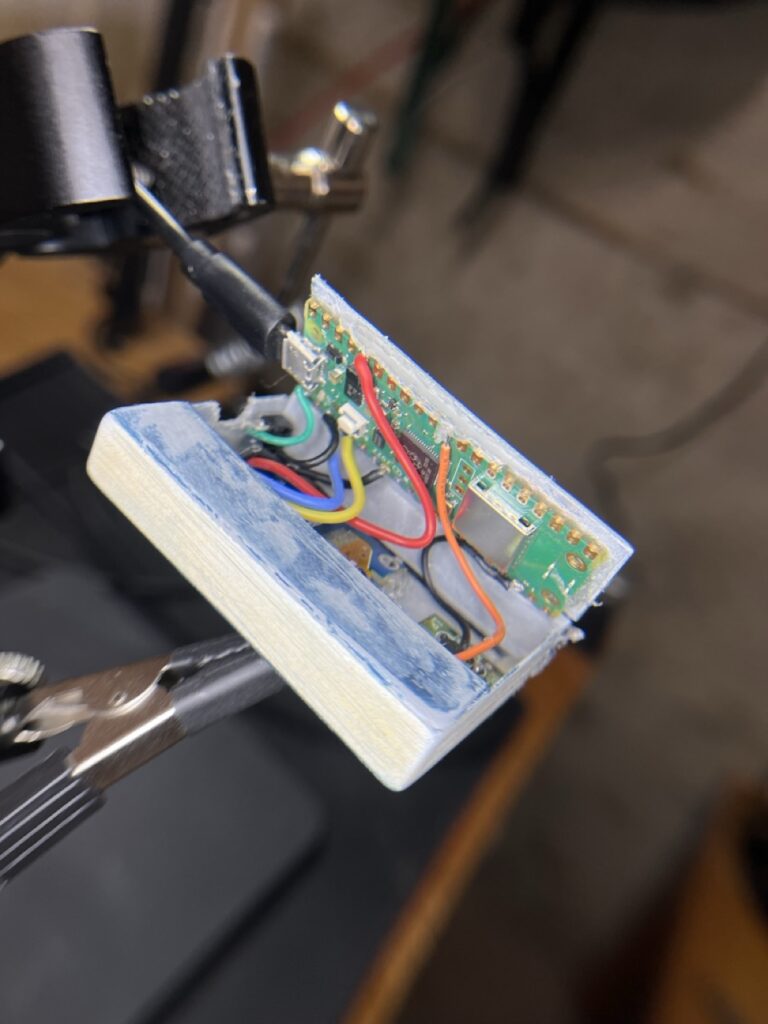

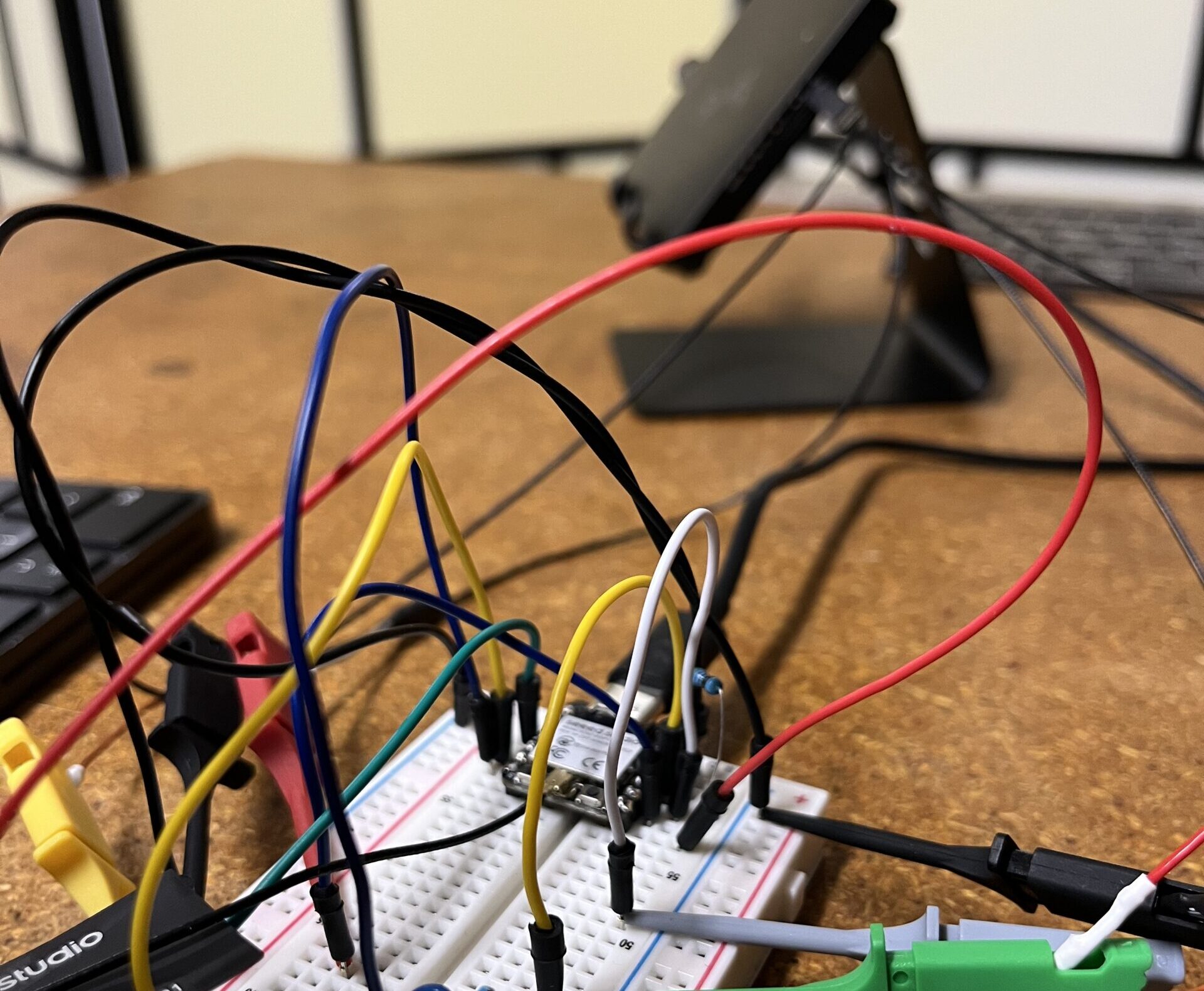

Communication Layer: ESP32-C3 devices implementing ESP-NOW protocol

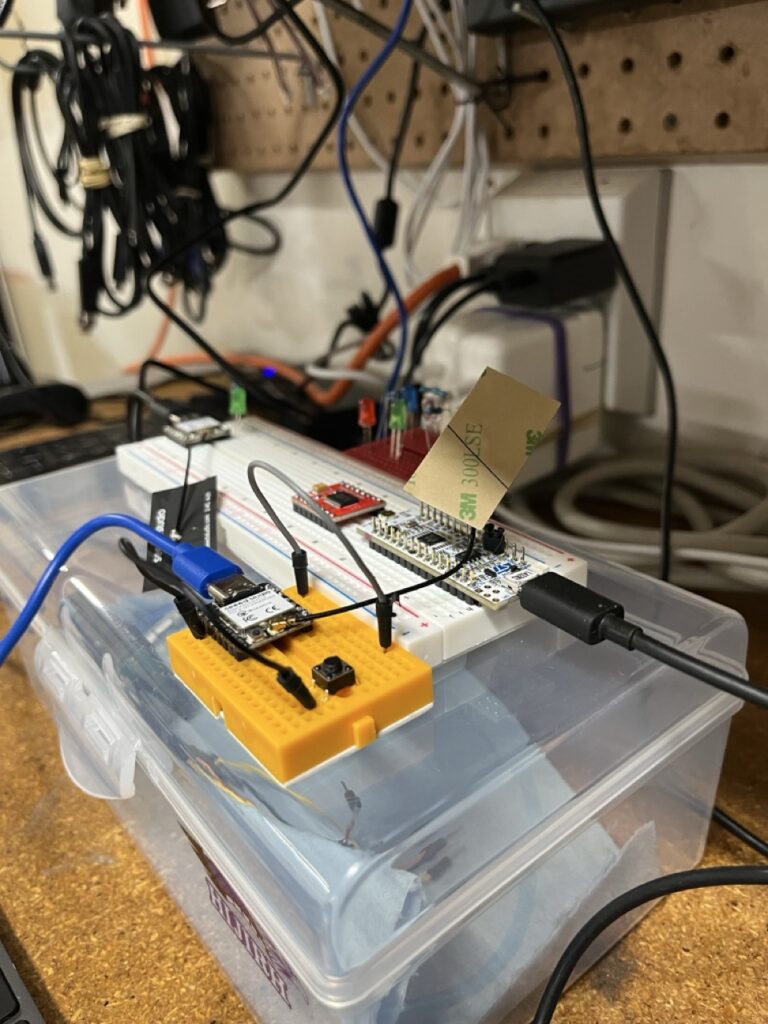

Motor Control: STM32L432KC with a TB6612FNG driver

Interface Protocol: SPI with DMA for high-speed data transfer

Control Input: Analog joystick with multiplexed ADC expansion

The rover represents three distinct engineering challenges operating as a unified system. Unlike previous projects that explored single concepts, this demanded mastery of wireless protocols, real-time motor control, and inter-processor communication simultaneously.

The Technical Evolution

From Simple to Complex Communication

The communication system evolved from basic ESP-NOW message passing to sophisticated 12-bit ADC transmission. Early implementations sent simple command tokens (LIGHT_ON, MOTOR_FORWARD) but rover control demanded continuous analog precision.

ADC Resolution Challenge: Transmitting joystick positions as 12-bit values (0-4095) required careful attention to byte ordering and data integrity. ESP-NOW’s packet-based nature meant each transmission needed proper framing and error detection.

Little Endian Encoding: ADC values split across byte boundaries demanded consistent endianness handling:

c// Transmit 12-bit ADC as two bytes

uint16_t adc_value = 2048; // Mid-scale

tx_data[0] = adc_value & 0xFF; // LSB first

tx_data[1] = (adc_value >> 8) & 0xFF; // MSB secondHardware Constraint Solutions

ADC Limitation Discovery: The ESP32-C3 provides only 3 usable ADC pins, insufficient for dual joystick control (4 analog axes required). This constraint drove the implementation of analog multiplexing.

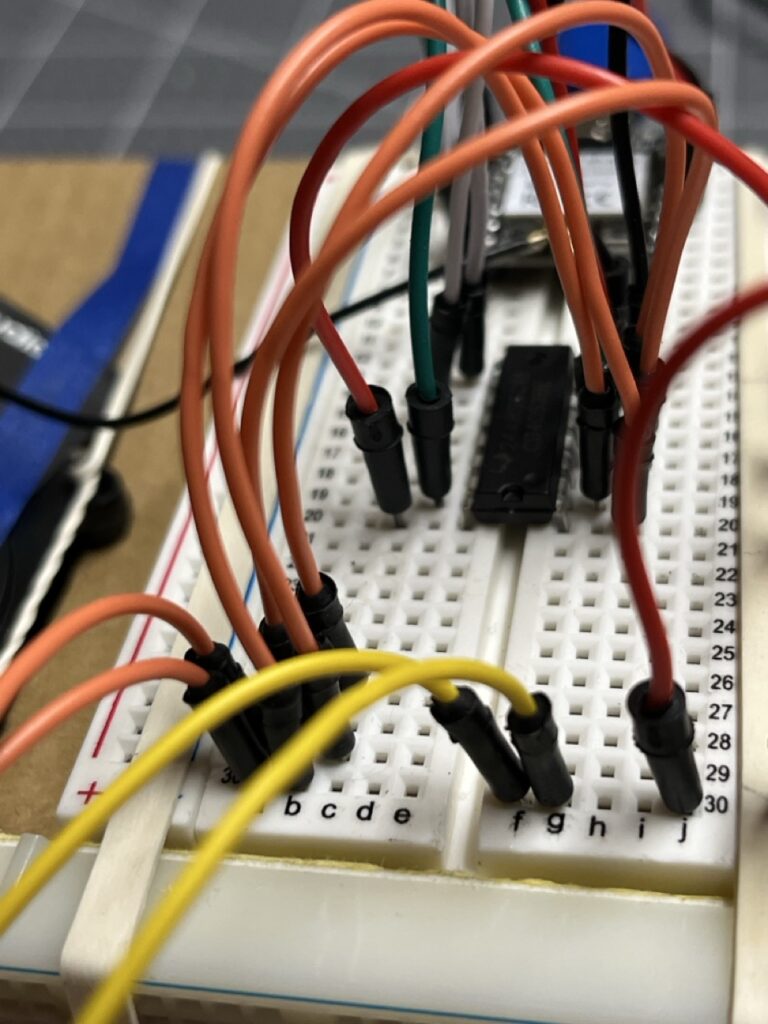

CD4053BE Integration: The triple 2-channel analog multiplexer expanded 3 ADC inputs to 6, enabling complete joystick interface plus auxiliary sensor inputs. The multiplexer selection logic required precise timing coordination with ADC sampling.

Multiplexer Control Sequence:

- Set digital select lines for desired channel

- Allow 10μs settling time for analog switching

- Trigger ADC conversion

- Store result with channel identification

- Advance to next channel

This seemingly simple expansion revealed the importance of analog signal integrity and timing precision in embedded systems.

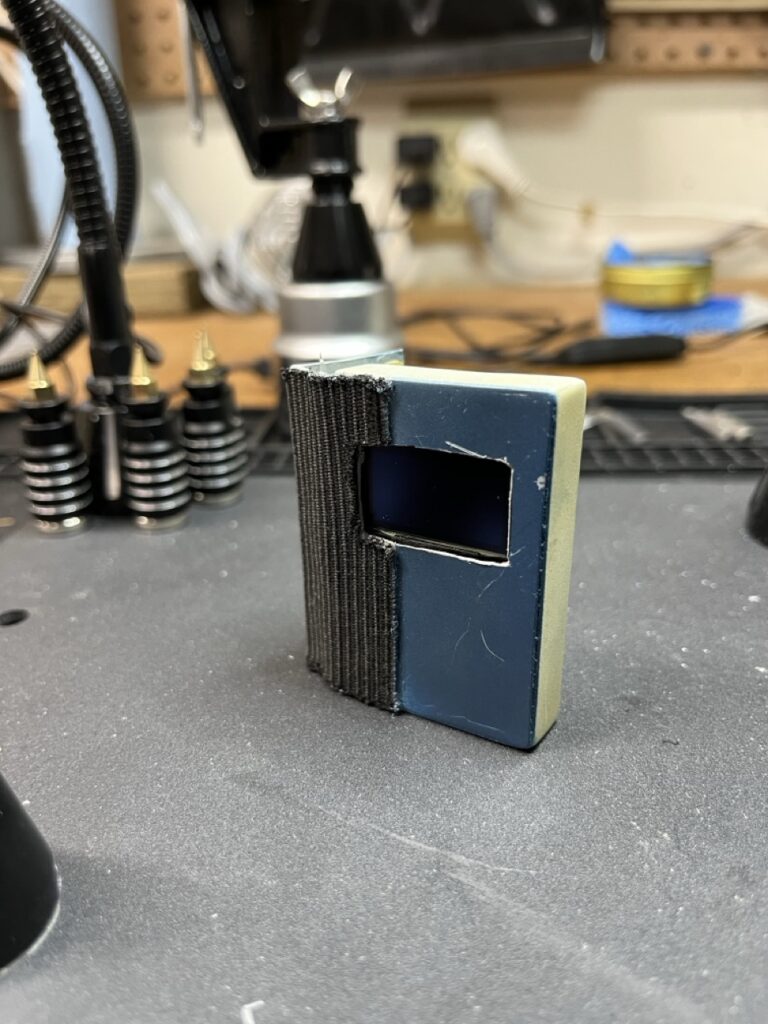

Motor Control Board Architecture

STM32L432KC Selection Rationale

Processing Requirements: Motor control demands real-time response to changing input conditions. The STM32L432KC’s Cortex-M4 core with FPU provides computational headroom for control algorithms while maintaining deterministic timing.

FreeRTOS Integration: Unified RTOS architecture between ESP32-C3 (native FreeRTOS) and STM32 (ported FreeRTOS) enables consistent multitasking patterns across the system.

Development Workflow Optimization: Previous experience with STM32CubeIDE revealed workflow friction with existing VIM-based development patterns. The solution: STM32CubeMX for initial code generation, then integration into CMake-based builds.

TB6612FNG Motor Driver

Bidirectional Control: The TB6612FNG drives two motors with independent speed and direction control. The rover’s dual-motor configuration provides complete maneuverability with a single driver IC.

PWM Speed Control: Motor speed regulation through STM32 timer-generated PWM signals. Frequency selection (1kHz) balances motor response with electromagnetic interference considerations.

Current Sensing: Driver IC current feedback enables torque monitoring and stall detection for advanced control algorithms.

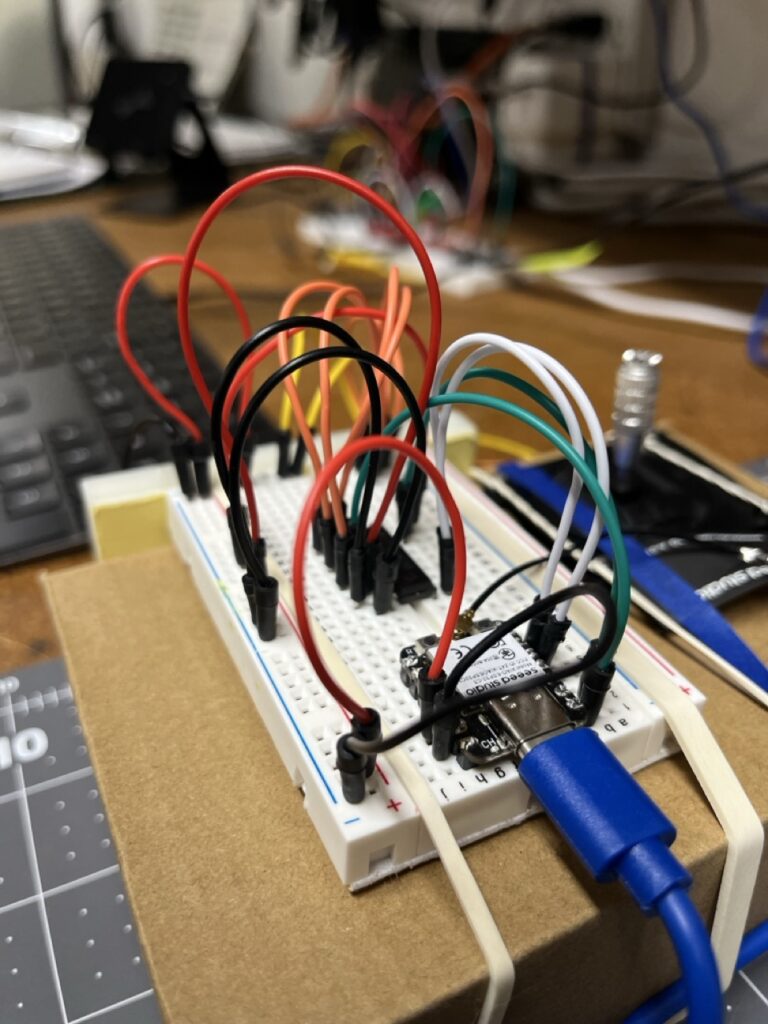

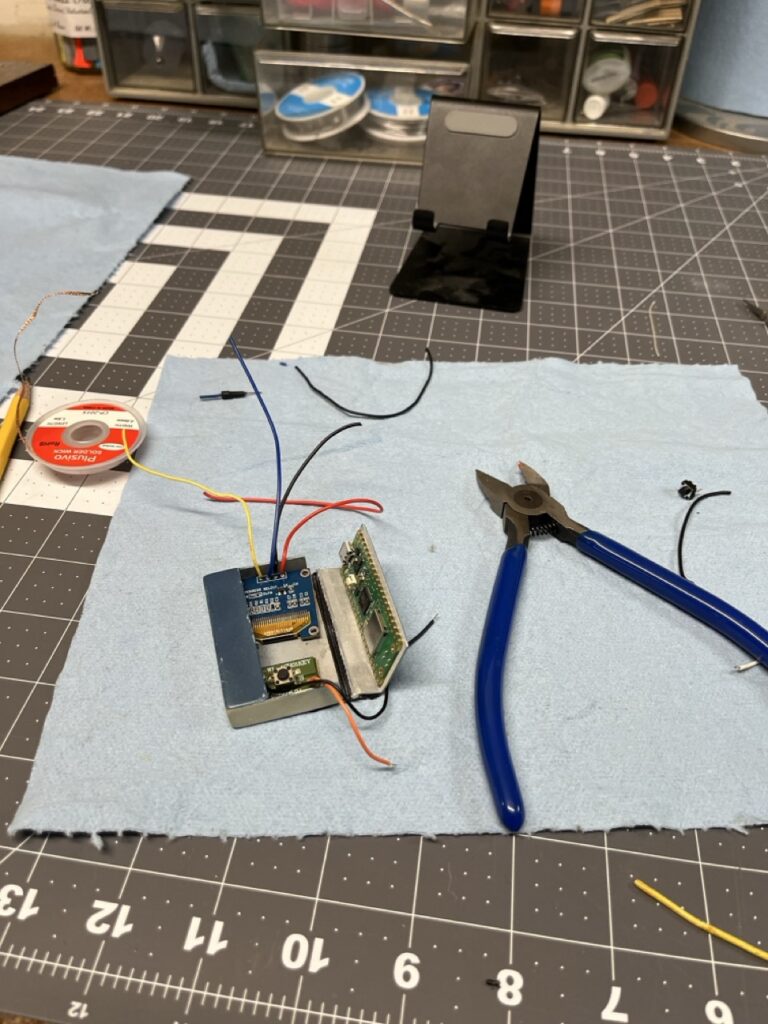

SPI Communication Protocol

Controller-Peripheral Architecture

ESP32-C3 as Controller: The wireless receiver aggregates joystick data and system commands, then dispatches motor control updates via SPI.

STM32 as Full-Duplex Peripheral: Motor control board responds to commands while simultaneously reporting motor status, current consumption, and sensor feedback.

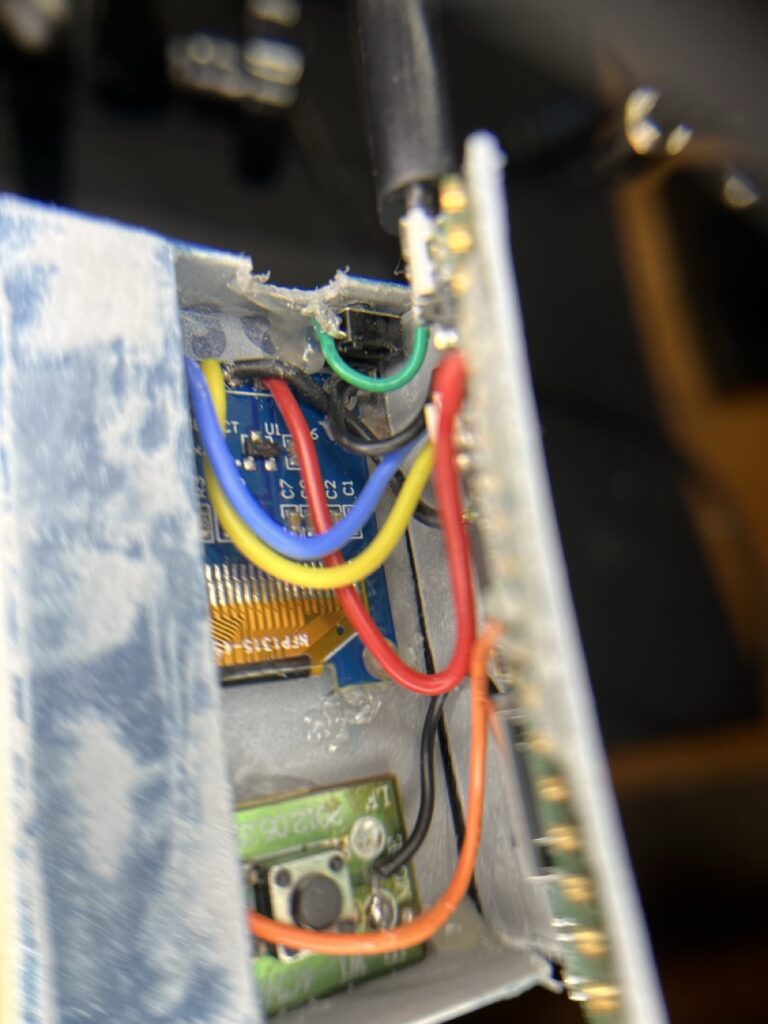

DMA Implementation Challenges

Buffer Overflow Mitigation: Initial implementations suffered data corruption during high-frequency updates. DMA buffering resolved timing issues but introduced synchronization complexity.

Packet Synchronization: Misaligned data reception required packet header implementation (0x1234 sync pattern) for reliable frame detection.

Manual Chip Select Control: Hardware SPI /CS proved unreliable for packet boundaries. External interrupt (EXTI) control of chip select provided precise transaction timing.

Engineering Methodology

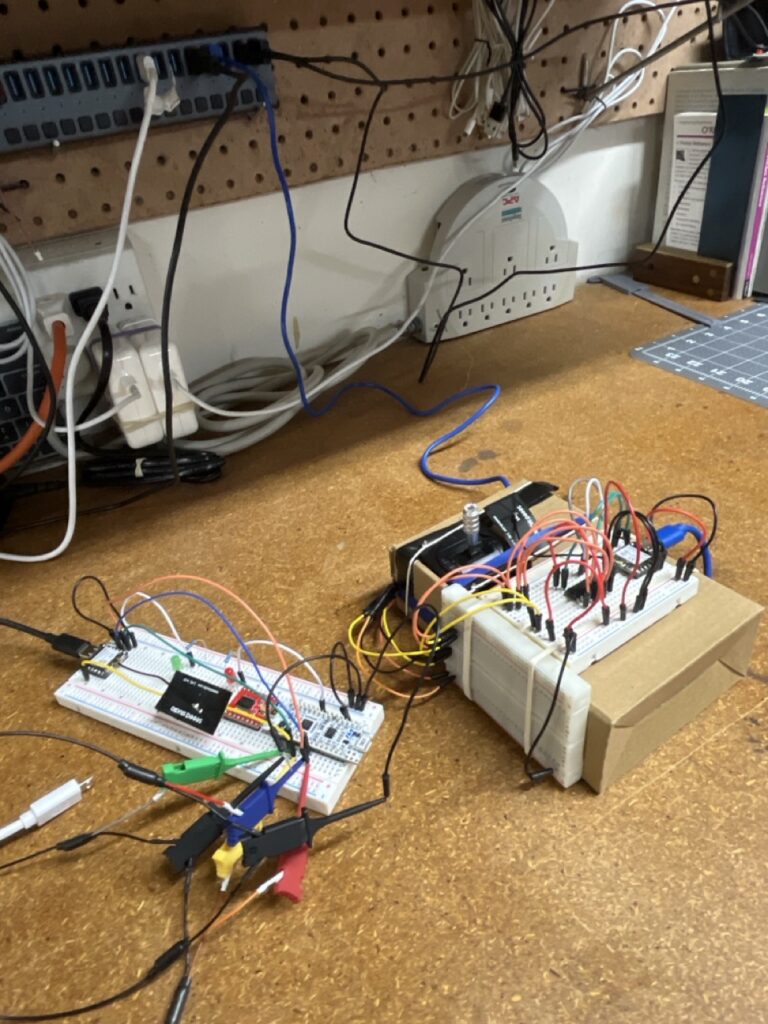

Iterative Development Approach

Component Isolation: Each subsystem developed and validated independently before integration. ESP-NOW communication verified separately from motor control logic.

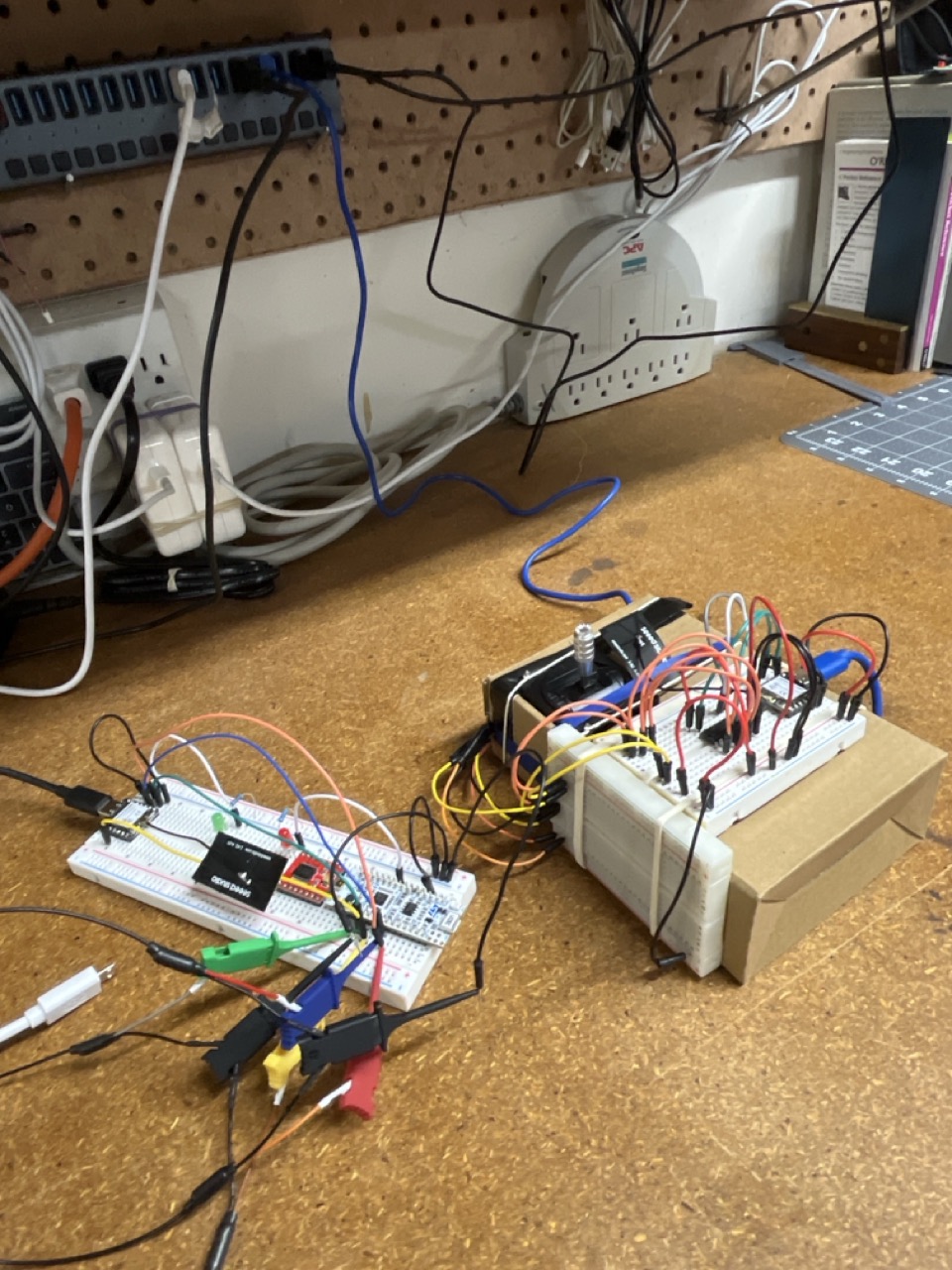

Logic Analyzer Validation: Every protocol implementation validated with logic analyzer captures. Signal integrity problems invisible to software debugging became immediately apparent.

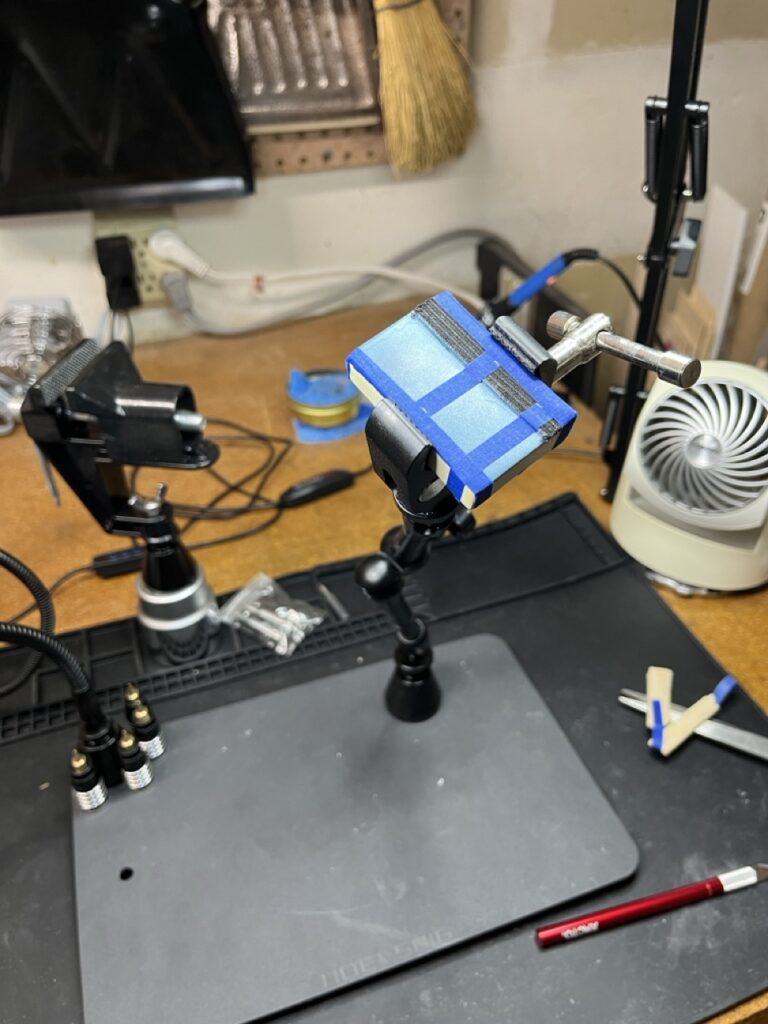

Documentation Discipline: Real-time engineering journal maintained throughout development. Every design decision, failed approach, and breakthrough documented with sufficient detail for reproduction.

Tool Integration

Development Environment: VSCode with CMake for both ESP-IDF (ESP32-C3) and STM32 projects. Unified build system across heterogeneous targets.

Debugging Infrastructure: OpenOCD and ARM GDB for STM32 debugging. ESP-IDF monitor for ESP32-C3 development. Logic analyzer for protocol verification.

Version Control Strategy: Shared repository for the time being as I develop and build mastery in embedded systems.

Current Status and Challenges

Operational Achievements

- ESP-NOW wireless communication established and stable

- ADC multiplexing functional with 6-channel capability

- STM32 motor control board responsive to SPI commands

- Single motor driver operational with PWM speed control

Active Development Areas

SPI Protocol Refinement: Packet synchronization and error recovery mechanisms under development. Current focus on robust communication in electrically noisy motor control environment.

Control Algorithm Implementation: Basic motor drive functional. Advanced features (acceleration limiting, coordinated turning, obstacle avoidance) planned for subsequent phases.

System Integration Testing: Individual subsystems validated. Complete system integration testing in progress.

Project Significance

The Earth Rover represents a convergence of multiple embedded systems disciplines: wireless communication, real-time control, analog signal processing, and inter-processor protocols. Unlike tutorial projects that demonstrate single concepts, this system demands simultaneous mastery of diverse technologies.

More importantly, it revealed how hardware constraints drive innovative solutions. The ESP32-C3’s ADC limitation led to multiplexer implementation, which sparked fascination with analog switching principles. This curiosity about fundamental logic operations ultimately catalyzed the DINO CPU project.

Engineering Philosophy: Complex systems emerge from the disciplined integration of well-understood components. The rover’s success depends not on exotic technologies, but on meticulous attention to interfaces, timing, and signal integrity.

The journey from simple ESP-NOW message passing to precision multi-axis motor control demonstrates how embedded systems engineering scales from basic communication to sophisticated control systems through methodical complexity building.